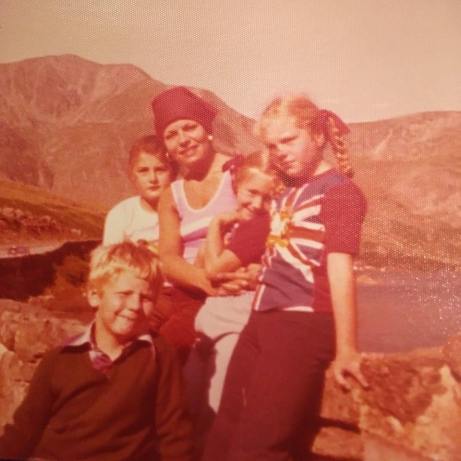

This is an old post, revisited in the time of Corona because I think so many of its lessons are now even more valid. In part this is because I am once again facing grief – my beloved aunt (there she is below, with my lovely cousins and me looking like a mardy brat behind her) passed away just as lockdown started – and although I am far more secure when I was in London or Brighton, these are scary and uncertain times.

So many of us are struggling in ways we couldn’t have dreamed possible only months ago and, with everyone in the same boat, it can be even harder to ask for, and accept help, because you feel you don’t deserve it: so many people are so much worse off, so what right do you have to complain? But I truly believe we need to come out of this different to how we went in – and part of that is to be more of a community. Which means not just helping those people you can help in whatever way you can do so – even if that is just sending silly memes to cheer up a friend who is home alone – but also letting those who are able to help you do so in the ways that they can. We need to become kinder to everyone, and that includes ourselves. Anyway, alas right now I’m not really in a position to help anyone except with my writing (though I do have a great stash of comedy memes, should you want them) so I hope this helps some people…

Kindness, Grief and the Art of Asking (from May 2016, edited slightly).

Three years ago, in May, I became homeless and an orphan in the same weekend. Both of those things are true, while at the same time, not true: factually accurate, emotively incorrect.

Only child of a single mother, I was indeed (to my knowledge – hi, Dad, if you’re out there!) an orphan, though that word conjures up sniffling and abandoned Victorian waifs or traumatised refugee children, and I was a grown-ass woman in her mid-40s with a pretty settled life. And though my relationship with my mother had often been fractious – inevitable, perhaps, when two strong willed, very different women live yoked together in sometimes straitened circumstances, with her need to protect me from the things she had suffered herself rubbing up against – occasionally with enough friction to catch fire – my own need to leave the town I grew up in and test myself and my art against the wider world – I was devastated by her loss. Without siblings, without a partner (and with a family I cared deeply for, but saw only rarely), I felt utterly alone.

Through the kind of cosmic coincidence that ensures that troubles indeed never came as single spies, at the same time I had to move out of the London flat I had lived in for over 10 years, and was faced with the crushing realisation that I could no longer afford the city where I lived. I’d quit my job to freelance, recognising if I didn’t my desire to write would always be smothered not by the needs of a job but more by my own inability to stick to the routines of 9-5 (or, this being London, 8-7.30) employment, and though my little publishing business was starting to take off, my income was erratic. Without a partner to rely on or access to the Bank of Mum and Dad, I found it difficult to find anyone who would rent a flat to me that didn’t look like it hadn’t been cleaned properly after the last murder. But I still felt a weird mix of shame and embarrassment when I referred to myself as ‘homeless’ – after all, I was staying on the sofas and in the spare rooms of friends’ (often very nice) houses. I wasn’t on the streets. Wasn’t I somehow making a grand claim that diminished the suffering of people who needed the sympathy more?

I’ve always prided myself on my independence: I wanted to be the bolshie, working class feminist who would (one day) prove that the restraints of a system that favours the wealthy and connected and, yes, the male, couldn’t keep me down. But the one thing that happens when your life falls apart and you realise you absolutely, absolutely cannot cope, is you simply have to ask for help. And you have to not be proud about where it comes from.

And so, I asked. In fact, I pleaded. My mum was a clutter fiend who lived in a council house. This meant it had to be cleared out fast: there was no luxury of time (and no payday at the end of it – in fact, because she died at the start of the month, I had to pay a month’s rent for the privilege of clearing it out). I didn’t have a car – I can’t drive – and I was living out of a suitcase. All of my own belongings were in storage, I was in no position to take possession of any more. So everyone who came to visit, I asked to take stuff: to the dump, the recycling, the charity store. My mum was a strong part of her community, and committed to good causes, so I was pleased that we managed to donate a lot of her things to a local refugee centre, but so much of the stuff had to be got rid of piecemeal. And so I lived, for a month, the weirdest of lives: knowing I had no home of my own, while dismantling around myself the place my mum, my life’s anchor, had called home for more than two decades. Every day something else went – the new Dyson hoover and the drier to a neighbour’s daughter who was starting a family, the TV to a friend’s teenage son – so I was constantly disoriented, not knowing what was going to be in any room I walked into, looking for things that were no longer there.

Swelled with the kindness of my friends and my mum’s neighbours, I headed back south. I still had nowhere to live, and the uncertainty of literally not knowing where I would be sleeping a week, even sometimes a night, ahead, frayed me: I’ve always been someone who craves security at home, even while I’m happy to live the rest of my life without it. But people stepped up in astonishingly generous – and sometimes just astonishing – ways. They let me ‘housesit’ their homes when they were away, pretending that I was somehow doing them a favour (one even left me a fridge full of prosecco and nice pasta as payment for looking after her cats). A woman I had only met once (on a friend’s hen night a full decade earlier) offered me her flat for a week when she was away. People I had not seen in years messaged me through Facebook offering me their sofas, their spare rooms, their parent’s holiday cottages or summer rentals. I was flat-out broke – struggling to keep my freelancing going in the face of all this upheaval, while saving for a deposit for somewhere to rent – and people cooked for me, bought me wine, and pretended not to mind or notice when I burst into tears on their sofa. It wasn’t everyone – some people I had thought were close friends simply froze me out of their lives (some never to return), my disintegration too much to deal with – but it was enough. In fact, it was plentiful.

(An aside: Not long after my mum died, I went to Glasgow – on a trip funded by a group of old university friends, who rightly and thoughtfully believed a train ticket would be a better idea than flowers for my mother’s funeral – and got the chance to reconnect with them. It turned out to be a poignant, but timely trip, as that very week one of that close knit crowd who had remained in the city after we all graduated was told that her cancer had returned, and was taken into hospital where, only a few short weeks later, she died, snuffing out a life that had been filled with brightness and warmth, and leaving the world a far colder and poorer place for her absence. And while I don’t want to talk too much about her death – her story is not mine to tell – I’ll always be grateful that through that serendipitous generosity I got to spend much of that week with her (a week in which she, breathless in her hospital bed, took the time to console me for my loss: such was the person she was, the size of her spirit). And I also saw how kindness creates communities, as her friends and family rallied to support her: the selfless and unshowy practical acts of friends banding together to keep someone else afloat.)

I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately – it’s that time of year, I guess. And also because I’ve been reading Amanda Palmer’s The Art of Asking: How I learned to stop worrying and let people help and it’s an inspiring read, but one that provokes introspection. Palmer is the kind of woman I admire but could never be – far more comfortable with chaos than I could ever manage (I read about the house she lived in, always bustling with strangers, and it literally makes me feel a bit queasy: I like my solitude, and my space). But she talks a lot about how art is an exchange, and how much of her early career was based on, basically, asking fans of her band to help them out, but how she also struggled when it came to accepting financial help from her husband, Neil Gaiman: the push and pull of the creative life. Of any life.

It made me look at how weird and self-conscious I can be about asking for help for my own work (‘oh, god, there she is: banging on about those stupid books again! FFS, we’re sick of it, shut up already. Does she think she’s actually good at this shit? Does she think she’s a real writer?’). It’s not something I’m comfortable with (I do it, slightly cringingly: ‘if you like my books, can you review them? Can you tell people? Can you read this blog post? Can you maybe come see my play? Click that link for me to get hits on a website so they’ll want to hire me more?’).

And yet, I’m always happy to support others: I’ve sat in cold churches in small audiences watching amateur plays, I’ve bought cheaply burned CDs and tweeted about friend’s rock bands – and I’ve been happy to do so. Look at me, supporting the arts! Being all cutting edge at the frontline of someone else’s creativity is actually an exciting thing to be. Why am I assuming I’m more generous and supportive (and whisper it, special) than anyone else? Or is that I secretly think everyone else’s art is worth supporting, but I’m just a big old fraud who risks exposure at every turn? Look at me! But not too closely, or you’ll see the cracks.

What makes this quandary even more ridiculous is that my life has been shaped by random kindness at every turn. Pretty much every job or gig I ever had has come from someone going: ‘Oh, my place is hiring, I’ll put in a word for you.’ ‘Oh, we need some writers, you could try out for the gig.’ ‘Oh, I know a small press publisher, your book might be perfect for them, I’ll put you in touch.’ From someone connecting with me on Facebook or Twitter or yes, even LinkedIn, wanting to hire me. A huge proportion of my work comes on personal recommendations: I can’t tell you how many emails I get that start ‘I was given your name by…’

And none of my current books – which I love working on and which give me enormous, visceral joy, even if only about 10 people ever read them – would ever see the light of day without my little bunch of supporters, who selflessly give their time and enthusiasm (and sometimes their very, very detailed notes) to make them better stories and get them out there. And who always seem happy to do so, and who hopefully get something enjoyable out of the process as well: whether it’s an early peek at the books, or just the satisfaction of helping, or the knowledge that they genuinely contributed: it might be my name on the cover, but there’s some of them in the contents.

So my point – maybe? Do I even have one? – is that we should be more open to the idea of asking for help, and receiving it when offered, and being as generous as we can when others are doing the asking, recognising that there’s something to be gained from being either end of that equation. But also that even the smallest of acts have ripples that can spread, the lightest of connections can blossom – a one-off interaction a decade ago might see someone offer you their home when you need it. Who knows? (You might never need it. But isn’t just that very possibility somehow wonderful?) And that that most of us already benefit more from everyday kindnesses than we realise, and we should celebrate that fact more often.

Like my writing? You can support me in a whole load of ways (some of them for FREE!)

If you’re skint: RTs and shares always welcome. Reviews of anything of mine you have read on Amazon or Goodreads or any book related/social media site, no matter how short, help boost profile. Tell your friends how lovely I am (leave out the needy bit.)

Donate to my Ko-fi. All the cool kids have one. (I am not cool, obviously, but have been assured this is true).

Buy my books: I’ve made all my books on Kindle 99p for the duration of the lockdown.

Rom-com with a dash of Northern charm: The Bridesmaid Blues

Paranormal adventure with snark and sexiness: Dark Dates: Cassandra Bick Chronicles: Volume 1

If you want to read something a bit darker, I just re-released by earlier novel Doll and my short stories No Love is This.

Want some swag? Buy a bag or a tee. And be sure to send me a picture! I’m on Instagram (@traceysinclair23) or Twitter (@thriftygal)